This weekend’s coverage in the San Diego Union-Tribune about two students who wrote an investigative report on Canyon Crest Academy Foundation illustrates a reality that was always very disappointing to me as a young person and scribbler of occasionally controversial ideas: namely, that schools ultimately don’t give a damn about student journalism if that journalism takes aim at the institutions of the school itself.

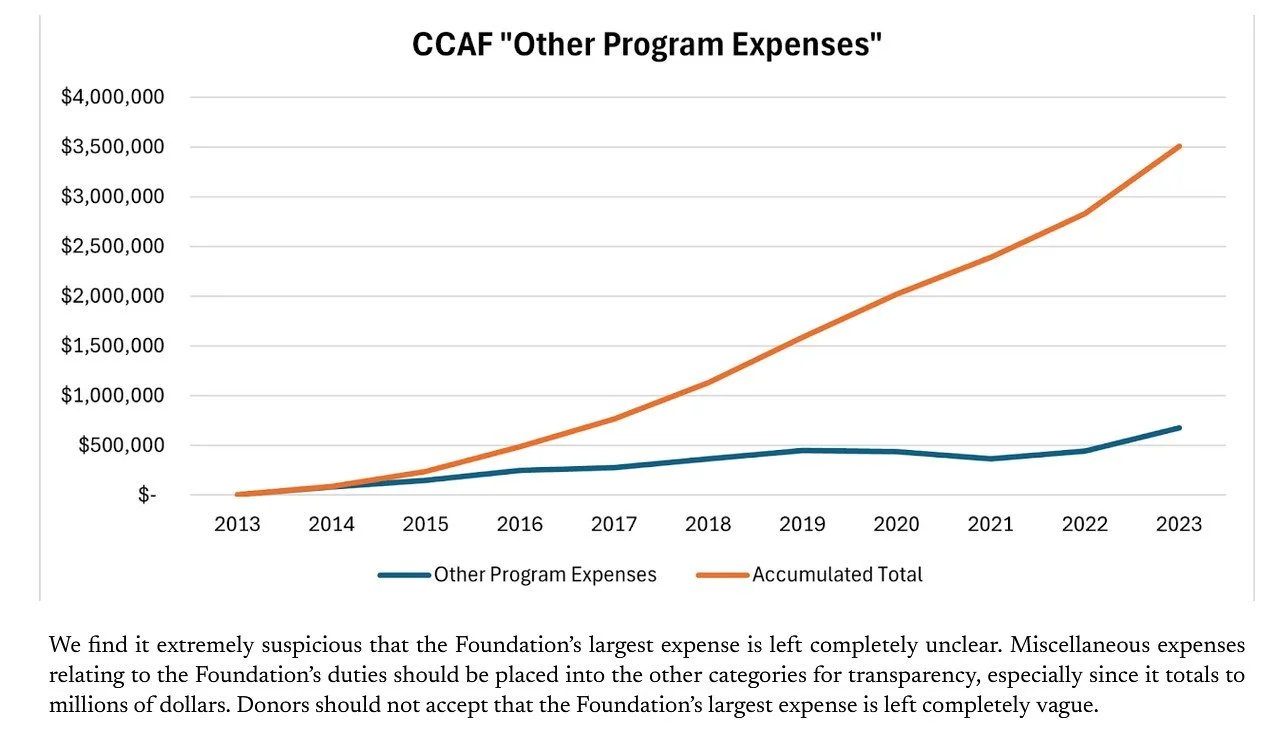

Up and Away: A graph from the students' report on the Foundation shows the ballooning of the amorphous "other" expense category over time.

Instead, schools who are the subject of critical reporting behave like most other corporations out there, and in fact they tend to be among the more shameless of corporate actors in their single-minded focus on only their own interests. So, instead of upholding values like transparency, or good faith debate about matters of public concerns, or, whatever other First Amendment-related ideal, they instantly circle the wagons, and blame the messenger. They do that even when doing so involves trashing the reputation of their own students.

In this case, the principal of Canyon Crest Academy has “condemned the report and reprimanded its authors,” according to the Union-Tribune, never mind that the report seems to have identified serious questions about the Foundation’s former leadership and accounting to the tune of several hundred thousand dollars. It is unclear if any formal discipline will be imposed, but the general approach of attacking the students’ reputation in the media is already, I would say, an adverse impact.

The principal is quoted as saying that “while the school board acknowledges the First Amendment’s freedom of speech protection, the board ‘also expects that all speech and expression will reflect norms of civil behavior on district grounds.’ ”

But the students are not on “district grounds”: their report is on an independent website. So what standards apply here?

In a way, this report is merely one example of a phenomenon that comes up frequently now in connection with social media, which is Internet posting by students about content that is school-related but which is not hosted on school servers or presented via school media. A very different variation on the same theme are the recent reports about deepfake pornography created by male students targeting female students, though that example does not involve the significant public accountability thread that is present in the Canyon Crest scenario.

Student speech rights are not as broad as those of adults, and can be regulated in certain ways (for example, speech advocating drug use is subject to limitation under the famous “Bong Hits 4 Jesus” case, Morse v. Frederick). When it comes to off-campus speech of the sort that is going on in the Canyon Crest case, the relevant question is whether the speech “ ‘might reasonably lead school authorities to forecast substantial disruption of or material interference with school activities.’ ” Wynar v. Douglas County Sch. Dist., 728 F.3d 1062, 1067, quoting Tinker v. Des Moines, 393 U.S. 503, 514 (1969). Such “substantial disruption” might be expected, for example, in the deepfake example or in instances of expressing racist or otherwise deeply offensive points of view about students or faculty. See, e.g., Chen v. Albany Unified Sch. Dist., 56 F.4th 708 (9th Cir. 2022).

On the flipside, a student’s mere use of social media to express a pointed general sentiment, such as “Fuck school fuck softball fuck cheer fuck everything,” does not give the school the power to imposed discipline, since that sentiment, even if it expresses “negativity,” is very unlikely to cause a “substantial disruption” or to interfere with anybody in particular. Mahanoy Area Sch. Dist. v. B.L., 594 U.S. 180 (2021). Here, the report on the foundation strikes me as being much more like saying “fuck cheer” (or perhaps “fuck the way this foundation is being run”) than any sort of potentially disruptive or improperly personalized content. In fact, if anything, the authors of the report seem to be performing the valuable function of standing up for integrity and transparency, not actually trying to disrupt anything at all.

And Thank Goodness: High school students do, in fact, have the First Amendment right to say "fuck cheer fuck everything."

Which means that, at least in theory, the school should probably not be trying to shut down the authors, and the perceived “civility” of the report, or lack thereof, does not change that fact. (By the way: does it uphold “civility” for adults to trash student journalists in the media?) In any event, surprisingly often it’s the case that schools, despite the role they potentially could play in setting an example around the importance of public debate, lash out first in response to critical speech, and only sort out the legality of their own actions after the fact.